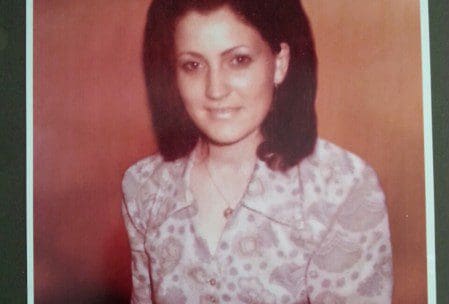

Remember Francis Arthurs.

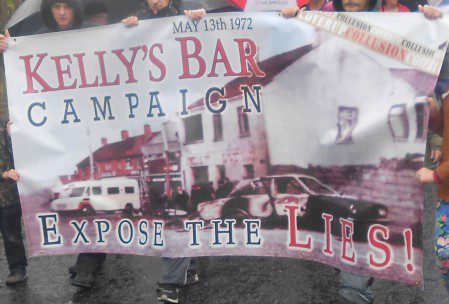

Francis Arthurs was one of three civilians who were abducted at illegal vehicle checkpoints by Loyalists, tortured and killed hours after Bloody Friday. His relative, Ciarán MacAirt, pieces together what happened that night from inquest files and secret British military archives.

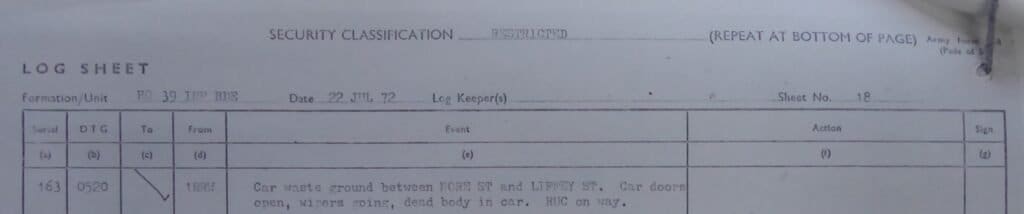

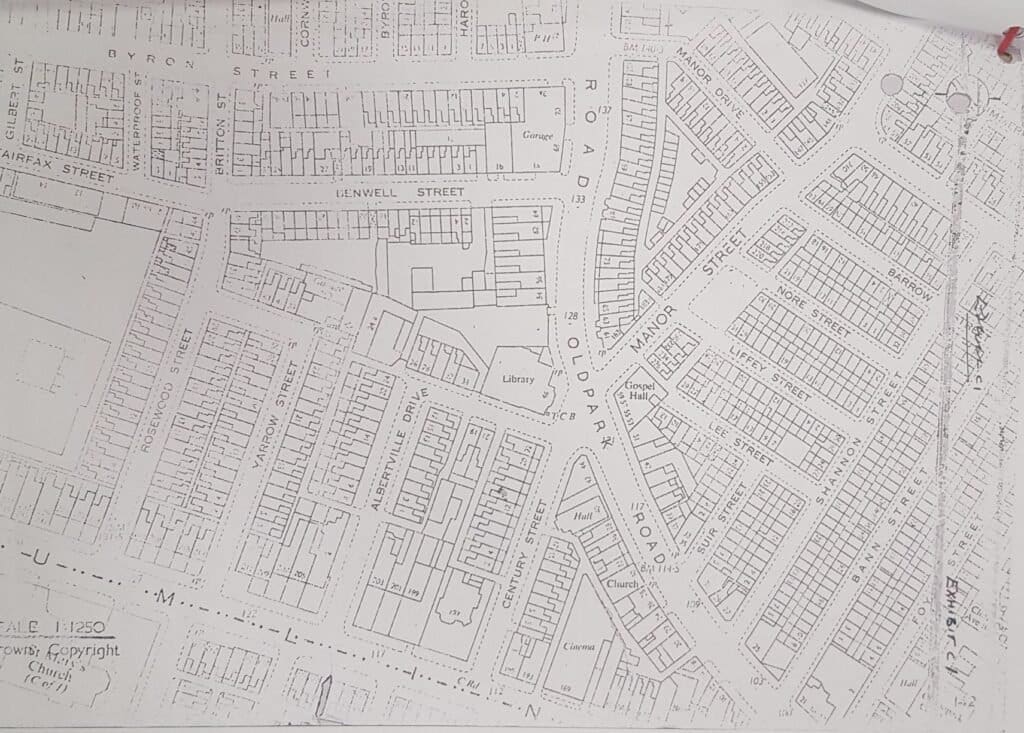

50 years ago this morning, the British Army discovered the battered and bloody body of a man at waste ground at the top of Liffey Street and Nore Street close to where the Crumlin and Oldpark Roads converge in north Belfast.

He is not named in the secret British Army files I found – neither when he is reported kidnapped nor when he is discovered dead.

It is as if he never existed or barely mattered.

His name was Francis Arthurs and he was a much-loved member of our family.

Bloody Friday had just passed. It had opened its bloody accounts just after midnight with the murder of Anthony Davidson in Clovelly Street, West Belfast, by members of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA). I know that as I have intelligence records of a UDA leader boasting to a commander of the Kings Regiment which of his men were involved. The files also prove that the British Army and Royal Ulster Constabulary were guarding his killer in a bed near to Anthony as he died but the killer was never arrested nor charged.

Few people outside of Anthony’s loving family and friends may remember his killing as its memory is swamped by what happened later that day when the Irish Republican Army (IRA) detonated 19 bombs across Belfast in a period of around 80 minutes.

At best it was foolhardy for IRA planners not to expect a major loss of civilian life when massive car bombs were primed and timed to go off within minutes of each other at commercial and transport hubs in and around a bustling city centre; at worst, the IRA did not care and counted any potential victims against the monetary cost to the British state as “collateral damage”.

9 men, women, and children were blown up and 130 injured – many of whom were maimed or forced to carry life-changing injuries for the rest of their days.

In a similar way to Anthony's, Francis's story was buried too.

A North Belfast man was shot dead on his doorstep later that night by the UDA. Again, we know that from the secret British military files as the same UDA leader boasted of that killing too – although the British Army had recorded the car leaving the area and knew where it went so also knew that it was a Loyalist murder. Nevertheless, the British armed forces allowed the family and public to believe that it was an IRA killing that sowed seeds of mistrust in the community from that day until this.

A member of the IRA, Joseph Downey, was killed that night too. In its own files, the British Army both claimed his killing and blamed it on a Loyalist incursion in the Market area – the British Army had been involved in a shoot-out with Loyalists in a car which included the wife of Gusty Spence, leader of the Ulster Volunteer Force. Again, the British Army withheld all of this information from the Coroner and family.

Information is the key – then and now.

It was at the end of this Bloody Friday, that Francis – or Frankie as he was also known – chose to meet his girlfriend for a couple of drinks at the Engineers Club in Corporation Street. (I have kept her name out of this article). Within the hour after midnight, they took a taxi to Ardoyne to drop her home and traveled up the Crumlin Road – one of north Belfast’s main arterial routes – with two other passengers.

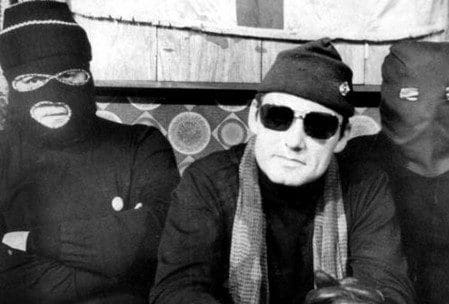

But at Yarrow Street, close to the Oldpark and Crumlin Roads' junction, around a dozen men stopped the car at an illegal vehicle checkpoint. Many of them wore combat jackets and one had a black mask over his face. It was a Loyalist area, so Francis’s girlfriend assumed they were UDA men.

One of the Loyalists demanded: “Any identification?” and the passengers fumbled in their pockets. He asked Francis where he was going and he told them Ardoyne – an Irish Catholic area.

The man then said, “Everybody out.”

Francis’s girlfriend was the last one out of the taxi and by then four men had Francis spread-eagled against a shop wall, frisking him. They found nothing, of course, and after a few tense minutes they let him go and he got back into the taxi beside his girlfriend.

He nearly escaped.

I only discovered this many years later when I accessed his closed inquest file – the open one has redacted the extent of his injuries and the scene of crime photographs.

As he sat in the taxi again, a man threw open the door and growled, “Right, out you.”

The Loyalists frog-marched Francis across the Crumlin Road and into the jaws of Yarrow Street. That was the last time that his girlfriend saw him alive.

The taxi driver drove them straight back down the Crumlin Road to Glenravel Police Station which was just over half a mile away or a couple of minutes by car. At that time it was also a base for the resident British Army battalion – the 40 Commando of the Royal Marines in July 1972.

They immediately reported Francis’ abduction to 3 RUC officers and a British soldier present who told them “This is a matter for the RUC.” One of the policemen said they would send out a patrol but as they sat there for another 10 minutes, the RUC officers did not call out a patrol nor leave to call out a patrol. They did nothing.

So bad was it in Glenravel, the taxi driver said to Francis’s girlfriend to come with him to Springfield Road police station in West Belfast where they made the same complaint again. The RUC there said they had no word of anyone in hospital and left Francis’ girlfriend sitting there as the taxi driver went home.

As she was sitting in the police stations, Loyalists were beating Francis relentlessly, asking him about any IRA he knew, then rompering him some more. He knew nothing but they tortured him for hours anyway before bundling him into the backseat of the car where they shot him dead.

When soldiers of the Royal Regiment of Wales found his broken body, he was slumped in the back seat facing upwards. His legs were sticking out of the open door, bullet casings in the seat well, and the window wipers still on, their blades like a hellish metronome when all else was still.

Only then did the RUC come.

Francis' girlfriend sat a few hours at Springfield Road Police Station and then visited Francis' house in Fallswater Street in the vain hope he was safely home. No one was there.

She returned to Springfield Road Police Station and waited a while longer for word but there was none.

Eventually, she made her way down Falls Road and into the city centre and went back home via Oldpark Road. At the bottom of Oldpark she passed on her right the waste ground where Francis' body was dumped...

If only Glenravel RUC had sent a patrol two minutes up the road, they would have driven into the illegal checkpoint, spoken with the Loyalists there, and saved Francis.

In her statement, Francis' girlfriend gave a good description of the man she believed was in charge at the illegal VCP and told police she would know him again: 30 – 35 years old, dirty-fair hair, close cut, around 5’ 7”, wearing a grey/blue two-piece suit. The taxi driver gave a similar description in his deposition of a man who spoke with him. He told police he thought he would know him again: about 30 years old, blonde hair, neatly cut, about 5’ 7” and wearing a suit.

I now know that the British armed forces were well aware that there were illegal Loyalist vehicle checkpoints on Crumlin Road, and that the UDA were stopping cars and accosting passengers.

I also know from secret British military files from this period that the authorities had a comprehensive dossier on scores of alleged Loyalist paramilitaries in the streets around the junction of Oldpark and Crumlin Road, including who led them and where they lived.

Their Officer Commanding lived just around the corner from Yarrow Street and was on the UDA’s Inner Council – one of the early leaders of the whole organisation. The British military knew all about him too as he is recorded as helping set up no-go areas a few weeks before and training Tartans, the younger Loyalists of the period. The intelligence files also record him as a member of the Ulster Defence Regiment too – a uniformed British soldier.

I examine these in my next article remembering Francis Arthurs on the 50th anniversary of his murder.